“Cikgu Shima!” a young girl cries for help, hobbling over on an injured foot. The girl is a stateless Bajau Laut child, who had stepped on a shell and cut herself.

Like all the other kids, she knew to promptly come to Iskul for medical assistance, and to look for Shima.

Shima calmly washed the wound. She medicated it and covered it up in a band aid. This has become routine for her.

This story is just one of a hundred.

Shima gets calls by grown-ups and children every day on Omadal. They are looking for medical help. She has a job teaching the stateless Bajau Laut children at Iskul Sama diLaut Omadal (Iskul). She also serves as coordinator. She is a Community Health Helper at Iskul’s Community Health Centre.

Shima provides more than just first aid. She administers basic medication for fever, headache, flu, scabies, boils, diarrhea, cough, and toothache. She treats patients of all ages, including infants.

She underwent two weeks of basic medical training at a clinic in Semporna, along with three other community members. She is now the backbone of our Community Health Center. Since July 2022, more than 536 cases have been seen there. This is out of a population of over 1000 people on Pulau Omadal.

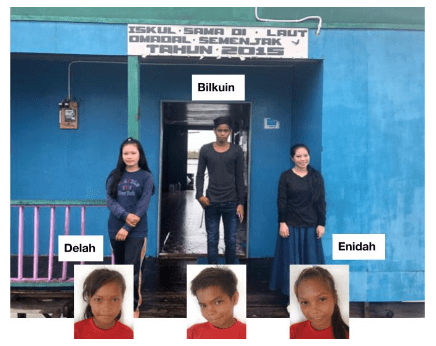

Photos: Shima at work and the cases she treats

Shima is 18 years old this year. Being a Community Health Helper is the closest that she can get to her dream. She wants to become a doctor or a nurse. She has given up hope of ever studying further in medical school. It is a disappointment, but a fact that she, like many in her community, has had to accept.

Despite being born to a Malaysian father, Shima has yet to be recognized as a Malaysian citizen.

She is stateless.

This is true no matter that her father is Malaysian. Her birth certificate lists her as a warganegara (citizen). Because of this, she was allowed to attend the primary school in Semporna. Yet, when it was time for secondary school, she could not register without an IC (identity card). She can’t obtain one.

Her mother is undocumented, and her parents are married only a religious ceremony. In Malaysia, it is not possible to register a marriage with an undocumented or stateless person. This remains true despite how common this occurrence is in Sabah. As a result, all children born from these marriages are considered illegitimate. This is because men can’t pass on their citizenship to children born out of legal “wedlock”. Malaysia is one of only two countries in the world with such discrimination. It discriminates against men passing their citizenship to their children born out of wedlock.[1][2]

In theory, Shima can apply for citizenship under Article 15(A) of the Constitution. Yet, to do so, she would need to update her birth certificate. If she attempted to update it, her birth certificate’s status would change to Bukan Warganegara (Not a Citizen). This change happened with her elder brother. He was then asked to apply for MyKAS or Kad Pengenalan Sementara (Temporary Identity Card). Why is the Jabatan Pendaftaran Negara (JPN) asking a child of a Malaysian father to apply for MyKAS? Why aren’t they offering citizenship instead?

Shima had requested to update her birth certificate with JPN in September 2022, when she was 16 years old. Now, two years later, she is still waiting for the call.

Shima will turn 19 next year. It is unlikely her birth certificate will be updated by the end of this year. Even if it were, she would NOT be able to apply for citizenship in time. She can’t apply under 15(A) if the current proposed Citizenship Amendment is passed in parliament this October. The current Constitution allows stateless children and youth to apply for citizenship up to the age of 21. Nevertheless, the Citizenship Amendment proposes to reduce the age from 21 to 18. If that happens, Shima will miss her rightful pathway to citizenship. What would happen to her then?

This means she would continue living in fear of being questioned by the authorities: “Do you have any documents?”. Police commonly ask this question in Semporna whenever they see anyone who looks disheveled. She would keep living as “the other”, one of those without documents, discriminated against simply for not having proper identifications.

She would not manage to live freely. She would not be capable of going wherever she wants. Instead, she would be confined to one place for the rest of her life. There would be no way for her to further her education or fulfill her dreams. Dreams? What dream? She would be forced to stay silent when wronged by others. It is not her fault. How can an undocumented or stateless person stand up for themselves? At best, they face the threat of being reported to the police.

Does she dare to fall in love and start a family? No, because she does not want her future children to be stateless and suffer like her. This cycle of statelessness will persist. The government must resolve its systemic causes. It continues to aggravate the problem, like the proposed regressive amendments in the Citizenship Bill.

It is imperative that the government addresses these key areas:

- Marriage Recognition: Allow the registration of marriages between Malaysians and stateless individuals. This will guarantee that children can inherit citizenship from their Malaysian fathers.

- Equal Rights for Fathers: Remove discriminatory laws that prevent unmarried fathers from passing citizenship to their children.

- Protect Citizenship Rights: Keep the current age limit of 21 for applying for citizenship under Article 15(A). This helps in avoiding further discrimination against stateless youth. Decouple the 3 regressive Citizenship Amendments.

- Amend Article 14: Allow equal rights to Malaysian mothers for their children born overseas.

There are too many Shimas in Sabah. We can’t allow these bright, incredible youths to be trapped by statelessness forever. Passing the regressive amendments in the Citizenship Bill will create more stories like Shimas’ in the process.

[1] https://www.equalnationalityrights.org/the-problem/ ( Barbados, Malaysia)

[2] Press Statement from The Office of the Attorney General. It declares that children born out of wedlock to Bahamian fathers and foreign mothers are citizens of the Bahamas.

Chuah Ee Chia noticed the harm that statelessness brings. It affects children born to Malaysian fathers with undocumented or stateless persons. It also affects children from the indigenous maritime community in Sabah.

She hopes that the Home Ministry will decouple the 3 regressive amendments from Citizenship Amendments. The government should tackle the systemic statelessness crisis in Sabah.